Stop Torture in Central Asia: It does not matter who our children are – no one has the right to ill-treat them

Tomorrow, 26 June, is the United Nations (UN) International Day in Support of Victims of Torture. And on this day the Coalitions against Torture in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the Association for Human Rights in Central Asia (AHRCA, Uzbekistan, based in exile in France), the Turkmen Initiative for Human Rights (TIHR, Turkmenistan, based in exile in Austria), the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (Poland) and International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) call on the governments of Central Asia to take action to put a stop to torture.

Across the world, this day provides an opportunity to remember victims of torture and their families, to listen to them and to unite to condemn this grave crime.

Relatives speak out

According to international law, torture is prohibited in all cases ,at all times and without exception and this prohibition cannot be lifted under any circumstances.

The mother of deceased torture victim Shamsiddin Zaydulloev (Tajikistan) gets to the heart of the matter when she says: “Nothing will bring my son back, but I would like to say one thing: It doesn’t matter who our children are – be they thieves, robbers, or drug addicts, they will always remain beloved children for their mothers. No one has the right to beat them. The law forsees a punishment for a crime. Once he atones for the crime, he should come back to his family, his children,”

Twenty-five-year old taxi driver Shamsiddin Zaydulloev was detained on 8 April 2015 on suspicion of drug trafficking. Few days later he died at the temporary detention of the Drug Control Agency. There are strong allegations that he had been tortured.

When Shamsiddin Zaydulloev’s mother visited him in the building of the Drug Control Agency, she recalled: “When I petted his head he said I shouldn’t touch the back of his head because it was swollen and painful. I asked him in a low voice whether he was beaten and he nodded. I kept asking him ‘If you are guilty of something, better to admit it and serve your term in the prison, than to be beaten here’. He said, ‘Mum, I’m just a driver, I am just taking the clients wherever they ask me , I did not do anything’.

For the next three days officials denied her access to her son under various pretexts. Early on 13 April, the family was informed that Shamsiddin was dead. His parents later told a lawyer working with the NGO Coalition against Torture that when they saw his body in the morgue it was covered in bruises and provided the Coalition with several photographs as evidence. On 25 April, the General Prosecutor’s Office opened criminal proceedings for “torture“. On 13 May, the parents and the lawyer were given the results of the forensic medical examination that was conducted after the autopsy, which concluded that Shamsiddin had died from pneumonia. A second forensic examination, ordered by the Prosecutor’s officer after the parents had appealed the first one, noted serious injuries. However, on 23 December 2015 the Prosecutor General’s Office closed the criminal investigation for “lack of evidence of a crime“.Shamsiddin’s mother appealed against this decision and proceedings were opened at the Sino District Court. After three years of fighting for justice for her son, the case was finally dismissed by the Court of Cassation in May 2018: which ruled that Shamsiddin had died of “acute bilateral pneumonia”.

Ongoing Challenges

Torture and ill-treatment continue to be widely used in all five Central Asian countries. Hundreds of individuals are charged and convicted based on confessions extracted under duress; and, fearful of suffering from reprisals, numerous victims of torture and their relatives do not lodge complaints. Lawyers, doctors and human rights defenders also risk harassment, intimidation and other reprisals when they speak out about torture. In all five countries, law enforcement and prison officials often prevent lawyers from visiting their clients and speaking with them in confidence, and the judiciary lacks independence. None of the countries has established independent mechanisms to investigate allegations of torture and many investigations are closed or dismissed despite overwhelming evidence of abuse.

The authorities of the five Central Asian countries fail to publish comprehensive statistics detailing the number of complaints, investigations, prosecutions and appeals in relation to torture and other forms of ill-treatment. In 2020 NGO Coalitions Against Torture recorded 225 new cases involving allegations of torture and other forms of ill-treatment in Kazakhstan, and 38 new cases in Tajikistan. In Kyrgyzstan the NGO Coalition Against Torture worked on 49 cases. In Uzbekistan the ability of human rights activists to track and record cases has been hampered by the fact that authorities have denied registration to independent human rights NGOs and limitations on their access to detention facilities, but the exiled AHRCA continues to receive credible allegations of torture on a regular basis. In Turkmenistan, the closed nature of the regime has made it impossible for activists to compile meaningful statistics but individual cases continue to come to light, such as the torture and ill-treatment of relatives of human rights activists living in exile.

In late July 2020, a group of four police officers in plainclothes came to the home of Babajan Taganov in the village of Agalan in Turkmenistan. Babajan Taganov is the brother of Turkmenistani human rights activist Dursultan Taganova, who now lives in exile. They took Babajan to the Serdarabat police department in the eastern Lepab region, where he was severely beaten and “punished” for his sister’s criticism of the goverment. On 15 August 2020, Babajan Taganov was hospitalised with a serious stab wound which he sustained in unclear circumstances while staying at a dacha close to the airport, with his 14-year-old brother. Some time before the incident, the police had asked aquaintances about their whereabouts. Relatives and friends who visited Taganov were later detained for questioning. The criminal investigation into Babajan’s stabbing was soon dropped.

In Kyrgyzstan, the authorities fail to implement international standards, in particular UN treat body decisions. As of 26 May 2021, the Human Rights Committee had adopted 34 views on individual complaints where it found Kyrgyzstan to be in violation of its human rights commitments ; 56 per cent of these cases involved torture and ill-treatment. To date, Kyrgyzstan has not provided official information on the measures taken to implement the Committee’s views and no effective implementation mechanism has been set up.

In the other Central Asian countries ineffective investigation of torture remains a problem. Under Kazakhstan‘s Criminal Procedure Code, reports of torture must be investigated immediately rather than being limited to a preliminary enquiry. However, in practice, cases are only referred for investigation after being registered in the Unified Register of Pre-Trial Investigations (UPRI) and in a large number of cases law enforcement officials have simply refused to register complaints of torture and ill-treatment in the UPRI.

In Tajikistan, amnesty laws are regularly applied to those convicted of torture offences. The conviction of three perpetrators in the case of Khasan Yodgorov is a recent example:

Khasan Yodgorov, a citizen of Tursunzoda, was forced to confess to a murder in November 2017 after he was beaten and tortured with electricity at the Tursunzoda Ministry of Internal Affairs (OMVD). His mother was repeatedly summoned after Yodgorovs arrest and forced to testify against her son under torture (police officers threw her against a wall and crushed her hand) and psychological pressure.

Six months later, Yodgorov was released from pre-trial detentionon 15 May 2018, after the real killer was caught. The next day, he filed an complaint against three officers from the Tursunzoda OMVD, and in October 2018, criminal proceedings were instituted against them. Their case moved to the Supreme Court in August 2019.On 17 June 2021 the three officers were found guilty of torturing Khasan Yodgorov and his mother and sentenced to prison terms of between 10 years and 13 years under Article 316 (excess of official authority), Article 323 (forgery of documents) and Article 143.1. (torture) of Tajikistan’s Criminal Code.However, the Supreme Court applied the Amnesty Act, thus reducting the sentences of two of the officers by a quarter. While the conviction of the three perpetrators is a positive development, the use of amnesty laws to people found guilty of torture clearly contradicts international standards.

Additionally, in Tajikistan, despite legal guarantees for human rights during arrest and detention, detainees are still often held incommunicado during the early stages of detention, without contact with the outside world. This is especially the case when it comes to those suspected of serious and especially serious crimes. Lawyers are denied immediate access to their clients and the staff of pre-trial detention centres still require written permission from the investigator or a judge, although recent legal amendments have annulled such requirements.

In Uzbekistan, many reports relate to torture and ill-treatment during the early hours or days of detention when detainees are held incommunicado. The lack of an urgent response mechanism to reports of torture, leads to the loss of evidence about torture. The expert group on the prevention of torture of the National Preventive Mechanism under the Human Rights’ Ombudsman was established in 2019 but so far has not proved independent or effective in preventing torture. Victims of torture, their relatives and lawyers who try to complain about torture find themselves exposed to harassment and worse.

Alexander Trofimov, 29-year-old father of two, is a good example: On 6 May 2021, Trofimov was arrested on suspicion of stealing money and was tortured by police on 6 and 7 May 2021 while being detained at Chilanzar District Police Directorate in Tashkent without contact with the outside world. Four or five police officers kicked Trofimov, hit him with truncheons and punched him on the head, body and legs, forced him to do the splits while officers took turns to jump on his back awhile his hands were handcuffed. Police allegedly told Trofimov that if he confessed to theft he would be released. They also threatened him with additional violence if he told his lawyer that he had been tortured or ill-treated. He was only able to meet his lawyer on 8 May, shortly before the remand hearing began. During the hearing the lawyer told the judge that his client had been tortured and requested that a medical forensic examination, but the judge refused. Only on 10 May was Trofimov transferred to a medical centre for examination and to date, the results of this examination have not been made available to Trofimov’s lawyer or relatives. Trofimov’s mother has sent several complaints to relevant authorities requesting an investigation into the allegations of torture of her son, and on 7 June 2021, the General Prosecutor’s Office launched an official investigation into the allegations of t torture – nearly one month after the events. Despite this, Alexander’s relatives have not been able to see him since 18 May and do not know his current whereabouts.

Over the past decade, the NGO Coalitions Against Torture in Central Asia have actively fought for redress for victims of torture and their families. Thanks to their efforts, compensation for moral damages has been paid to victims of torture (or the families of the deceased) in some countries. While these developments have set important precedents, the amounts of compensation paid are often inadequate and not commensurate to the gravity of the crime of torture.

In a recent case from October 2020 brought by the Tajikistani Coalition Against Torture, the court dismissed a compensation claim on the grounds that the Ministry of Internal Affairs declared that it was “not responsible for the unlawful actions of its employees”, and that the “damages incurred should be recovered from the perpetrators”.

To date, the UN Committee against Torture and the Human Rights Committee have issued 16 views on cases involving torture from Kazakhstan. However, in only three cases has compensation been paid to applicants: Bairamov 197 EUR (100 000 Tenge), Gerasimov and Rakishev 1970 EUR each (1 million Tenge).

Positive developments

The saying “A constant drip wears away stone” epitomises the persistent work of civil society groups in Central Asia. Anti-torture coalitions and human rights NGOs have supported many victims in their struggle for justice. They continue to urge national authorities to eradicate torture and to advocate for change on an international level.

Thus, despite all the challenges ahead and the still entrenched practice of torture, there have been some rays of hope:

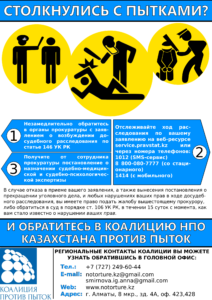

For example, after persistent calls by the Kazakhstani Anti-Torture Coalition about the need to strengthen domestic legislation against torture, the Coalition is now working with the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Kazakhstan, the Office of the Prosecutor General and the National Human Rights Centre on concrete proposals for the improvement of national legislation.

In May 2021 Turkmenistan amnestied 16 Jehovah’s Witnesses convicted for conscientious objection, the overwhelming majority of whom had reportedly been beaten and tortured in detention.[i]

Kyrgyzstan has made some progress in compensating torture victims. For example, in February 2021, the Jalal-Abad Regional Court upheld a decision of the Aksy District Court which awarded compensation to torture victim Maksatbek uulu Samarbek on the grounds of “ineffective investigations into an allegation of torture”.

Tajikistan increased penalties for torture in domestic legislation and strengthened detainees’ and prisoners’ rights. Anti-Torture coalition members welcomed also the adoption of the penitentiary reform programme and its action plan with the broad involvement of Tajikistani civil society groups.

The authorities in all Central Asian countries must acknowledge the scale of the problem of torture, publish comprehensive statistics on cases and investigations, allow independent monitors full access to detention facilities, enter into genuine cooperation with relevant UN mechanisms and address entrenched systemic problems in a transparent manner. Concerted efforts by states are still needed if torture is to be eradicated.

Свежие комментарии